This column, from the weekly opinion piece MATTER OF FACT, first appeared on BrooklynReporter.com, and in the Home Reporter and Spectator newspapers dated August 14, 2020

August 7 was the deadline for parents of children in New York City schools to officially register their choice for the means of learning they want their kids to receive this fall. Anyone wanting 100% virtual instruction, rather than the default blended learning model, needed to make that preference known on the Department of Education’s website.

For most families, this was a complex decision and there are myriad issues at play. There are essential workers, including teachers, whose jobs do not permit them to be home while their kids attend virtual class. There are children who are food insecure or without a permanent home, who rely on schools for basic needs.

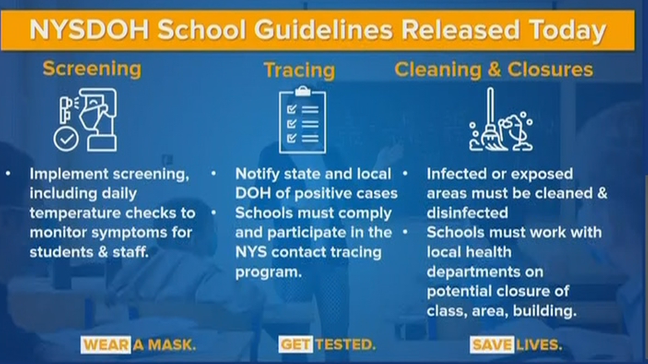

Also on August 7, Gov. Cuomo announced that schools in the state could reopen, given they meet certain criteria. There is no doubt that remote learning is not equivalent to in-person classroom instruction, but the health and safety of school children, teachers, and faculty must be everyone’s focus.

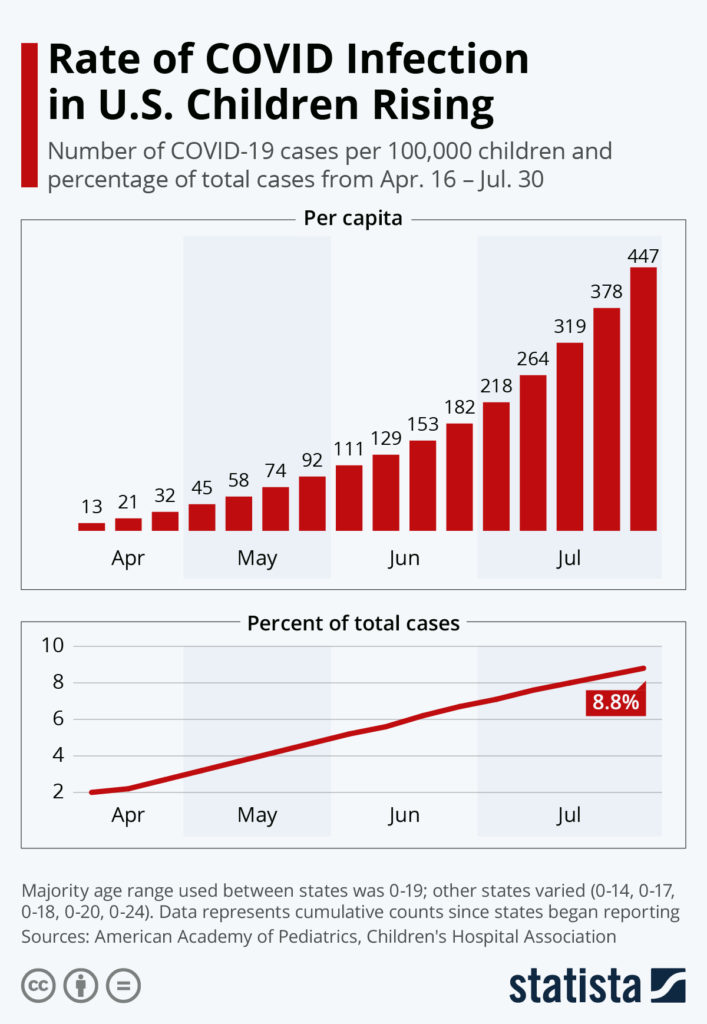

Many say that children contract the virus at a lower rate and tend to have a much lower incidence of serious effects, and although statistics do indicate that COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations have been lower among early-age demographics, it is still unclear as to why that is.

It may be possible that kids are less susceptible to acquiring the virus, but it may also be possible that since schools and daycares were all closed very quickly at the start of this pandemic, children have not been in environments where they have had an opportunity to contract it.

A recent review of state statistics by the American Academy of Pediatrics and Children’s Hospital Association found that during the last two weeks of July, at least 97,000 children tested positive for COVID-19. If nothing else, these figures dispel any notion that kids are immune to the virus.

A week ago, photos posted online of crowded hallways at Georgia’s North Paulding High School received widespread attention. Within a few days, the school had moved to online learning, after several students and faculty members tested positive for coronavirus.

“Will it be acceptable if we have dozens of children hospitalized after contracting the virus in school? If a teacher dies? If a student dies?”

In late June, a sleepaway camp in Georgia had a mass outbreak, with nearly 300 confirmed cases of COVID-19 among its campers and teenage staff members, with the highest infection rate actually being amongst those 10 years of age and under.

Hard data as to how easily young children acquire and spread the coronavirus has yet to be compiled, but an extensive South Korean study found that students 10 and older appear to spread the virus at about the same rate as adults.

There is just so much that we do not know. But what do we know? New York City schools remained open for the first two weeks of March, as the coronavirus outbreak accelerated, before moving online. With just that short period of time where schools remained open, less than two months later, over 70 Department of Education employees had died from COVID-19.

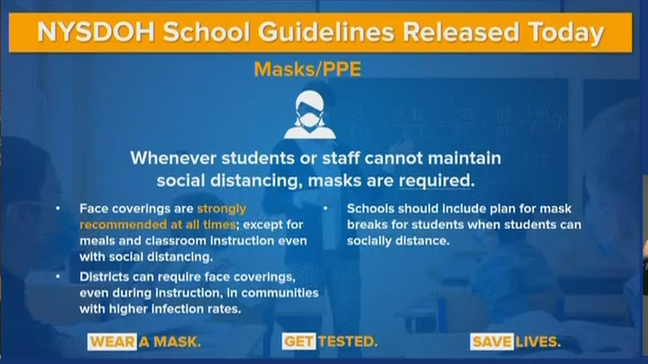

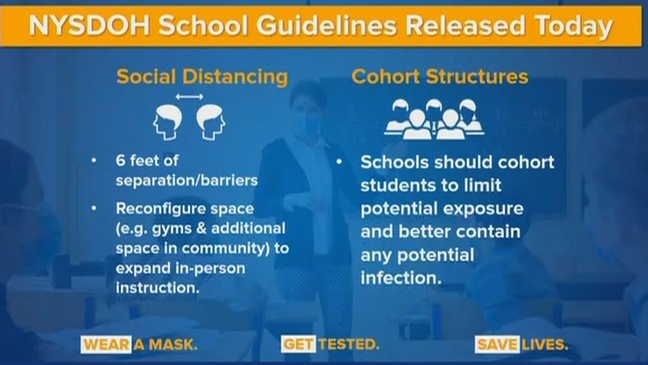

Granted, March was a long time ago and before schools were shuttered in the spring, they were operating as they always had. But how confident are we that all kids will be able to keep their masks on all day, every day, and maintain six feet of social distancing at all times?

If children are attending class in-person two or three days per week, what do their working parents do on the other days? If kids are constantly told they need to stay away from other kids and that they are not allowed to leave their desks for the entire school day, are they actually going to be receiving the benefits we want them to get out of being around their classmates and teachers?

City Schools will open given the city’s positivity rate remains below 3%. It has been consistently hovering at 1%. Even if one-third of students are on a fully remote learning schedule, if just one-quarter of one percent of the students attending in-person contract the virus, that is nearly 2,000 kids.

Will it be acceptable if we have dozens of children hospitalized after contracting the virus in school? If a teacher dies? If a student dies?