This column, from the weekly opinion piece MATTER OF FACT, first appeared on BrooklynReporter.com, the Home Reporter and Spectator dated April 30, 2021

Minneapolis Police released a statement on May 25, 2020, the day of George Floyd’s death, which mentioned that he physically resisted arrest and that after they got him into handcuffs, officers noted he appeared to be in medical distress and called an ambulance. That was it.

There was no mention of Officer Derek Chauvin kneeling on Mr. Floyd’s neck for over nine minutes. Nothing about the 28 times Floyd said, “I can’t breathe.” Not one of the multiple members of law enforcement at that scene reported Chauvin’s actions.

If it were not for seventeen-year-old Darnella Frazier videoing the nine-minute lynching that she watched in broad daylight, despite many people having witnessed a slow public execution, George Floyd’s murder would have been brushed aside and Derek Chauvin would be on patrol today. She and the other eyewitnesses of this murder testified to how difficult it has been living with the knowledge that they watched a man be killed steps from them and could not stop it because the perpetrator was a police officer.

It is not the case that there is something inherently wrong with every person who chooses to become a member of the police force. There are good people who would never needlessly employ lethal force, who choose this profession, but there is a systemic problem that even the so-called good apples are a part of.

Members of the police, as well as their most ardent supporters, often say that the stories receiving media attention where an unarmed person of color is killed by an officer who goes too far are relegated to just a few bad apples. The good apples of law enforcement, who agree with the guilty verdict for Chauvin, say that they should not be lumped in with him or what he did. In other words, they are saying it is not right to generalize them and assume they are dangerous to someone else’s safety, something which people of color have been saying for years in response to how they feel they are treated by the police.

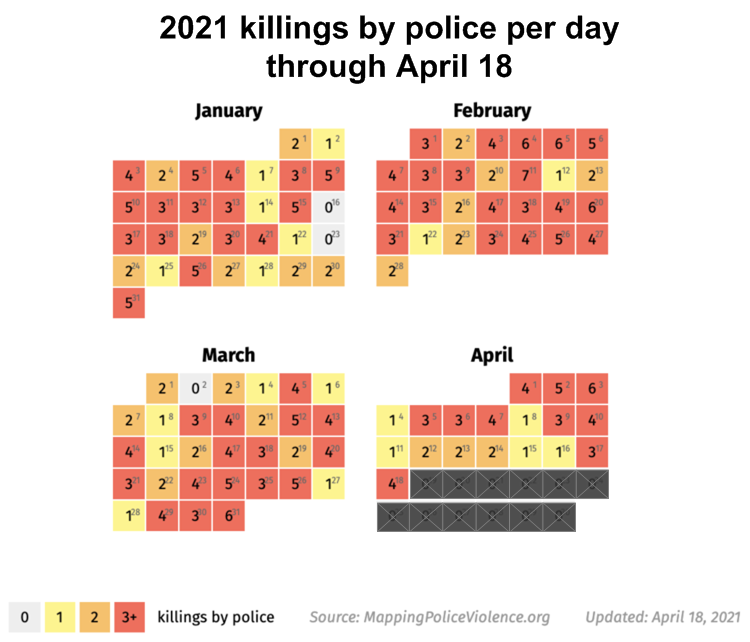

In the twenty-four hours following news breaking on April 20 that the jury had reached a verdict in the Chauvin trial, there were six people killed by police across the United States. That was just one day and the circumstances in these cases varied greatly, but it was not an aberration.

From the beginning of this year through the day of the Chauvin verdict, there were only three days where someone was not killed by police. On 65 of those 110 days, police killed three or more people. Over the past year, 985 people have been killed by police.

A 2016 Analysis of deaths due to use of lethal force by law enforcement posted on the U.S. Health and Human Services website, shows that victims were disproportionately black, with a fatality rate 2.8 times higher among African Americans than whites. By a significant margin, black victims were more likely to have been unarmed than those who were white. A 2018 study by Northwestern University found that about 1 in every 1,000 black men can expect to be killed by police.

Nearly one-quarter of all cases where police killed someone, were mental health related, with about one in five of those suspected to be incidents of suicide by a cop. The current system is not only leading to officers using deadly force against citizens who require psychiatric help, it is resulting in cops committing suicide at alarming rates, with a 2019 study by the Addiction Center finding that the suicide rate in law enforcement is the highest of any profession. Even in instances where officers are killed in the line of duty by someone else, black officers, who comprise 11 percent of law enforcement, account for a disproportionately high fifteen percent of those murdered.

The most immediate step we can take to address this broken system is to ensure more accountability. The first amendment protected Darnella Frazier’s right to record Derek Chauvin, but far too often, citizens are threatened to stop filming. New York’s Right to Monitor Act, signed last June, further protected that right, but legislation should be passed to punish officers who violate someone’s right to record.